Reflections from the “Technology and Creativity in Literary Translation” workshop – by Marco Maria Baù (translator CZ – IT)

As a master’s graduate in “Languages, Communication and International Cooperation”, it took me only a few minutes to choose the workshop “Technology and Creativity in Literary Translation” among many others offered by the CELA program. Having translated a wide range of texts throughout my academic career, I wanted to gain deeper insight in the ever-evolving world of intelligent machine translation. Over the course of our three workshop sessions with Professor Ana Gueberof, we have examined the complex relationship between human translators and the computer software that increasingly defines our profession. Far from offering simple answers, these sessions uncovered fertile ground for questioning the application of CAT tools, machine translation, creativity, and human judgment—especially in literary translation.

The first class provided an overview of leading Computer-Assisted Translation (CAT) software currently employed, such as RWS Trados Studio, Wordscope, Matecat, Wordfast, MemoQ, OmegaT, Phrase, and Linguee. These tools are designed to enhance productivity through the inclusion of features like translation memory, management of glossary, and compatibility with various file formats. However, while the tools are widely used in business and technical translation settings, use in literary translation is minimal—and in our classroom, largely absent.

None of the other translators on my team reported using CAT tools in literary translation, and that is significant: literary translation is a discipline where tone, rhythm, nuance, and cultural connotation are more valuable than speed or consistency. The automatic suggestions provided by CAT tools are likely to break down when it is a question of finding precise synonyms that have the tone and register of a complex literary text. The danger of perpetuated error—most especially from improperly aligned open-source corpora—only makes this more of an issue.

In such situations, more conventional lexicographic resources such as thesauruses are more helpful than plain dictionaries because they offer a selection of meanings, and translators may choose words not just by denotation but also by emotional connection and stylistic fittingness.

We also mentioned the potential use of bilingual and multilingual corpora, namely for literary translation. Where CAT systems may be insufficient in literary fields, corpora might be capable of showing which of some idioms, metaphors, or culture-specific mentions have been rendered in real environments. Parallel corpora (like Europarl, DGT-TM, and OPUS) exist here, having source and target texts matched, while similar corpora present a general image of stylistic and structural affinities across languages. Those may supplement the translator's sense rather than usurping it.

Professor Ana Gueberof starts the second lesson by making an incredibly intriguing remark on the dynamics between AI software and writers/translators: "it is evident that a human writer or translator still does better than AI-based engines, but keeping in mind the recent socio-technological development, one should be able to gather a number of different reasons and references which demonstrate the unmistakable supremacy of the human work". She then speaks about her own experience with this issue, saying that "not everyone realizes how writing and translation occurs" because most people still believe that, today, any translation can be accomplished by "simply pressing a button". We then switch gears to the topic of "creativity and AI" by talking about how creativity is a new social phenomenon, i.e., during the renaissance times, creativity was limited to the few geniuses who existed (Michelangelo, Da Vinci etc.), while in today's times anybody can be considered creative. Ana says that creativity is everywhere, "illusive concept which was studied/scientifically acknowledged only from the mid-20th century onwards"; Then, went into the four dimensions of creativity that are particularly translatable to translation: fluency, i.e. the capacity to generate several possible solutions to a translation issue; flexibility, as for choosing the best contextually appropriate option among the solutions; originality, namely bringing in new linguistic or structural features, and elaboration, i.e. expanding and enriching the translated phrase.

They are specifically pertinent when dealing with literary translation, wherein the translator often finds herself being assigned a sort of second authorship. Such capability, however, does not come with tools utilizing AI because these do not carry with them genuine evaluative judgment capability. Such, according to Ana, can create products mimicking creativities but is never capable of deciding contextual usefulness or appropriateness. Machines neither ask questions but only reply on the basis of statistical foretelling.

During the breakout sessions, we debated whether creativity is necessarily a good thing, particularly with AI innovation being spearheaded mostly by private technology firms. The class consensus was that while the product of AI may appear creative, the process to them remains algorithmic and lacks self-awareness, intentionality, or cultural embeddedness that defines human creativity.

Session three covered the assessment of MT output. We began by distinguishing between human evaluation processes of main and automatic ones such as BLEU and more recent neural models like COMET, with a focus on the concepts of adequacy and fluency. Adequacy in terms of whether or not the MT output is as meaningful as the source, fluency as the consideration of grammaticality and idiomaticity in the target language.

Verity and MQM (Multidimensional Quality Metrics) were said to provide more detailed evaluation through annotated error types, but at the expense of taking more time. More recent approaches, like COMET, employ human judgments-trained neural networks for imitation of evaluation. These are promising but are limited in terms of interpretability (they are "black boxes"), high computational cost, and sparse language coverage.

We also discussed post-editing effort—the mental and time effort required to make MT output publishable. Automatic metrics are fast and cheap, but lack accuracy at the sentence level.

Human assessment gives more valuable information but is slower, more subjective, and more expensive.

The point here is that machine scoring is aided by human grading, i.e. what type of text—a field of discourse, genre, or intended reader—it is ought to inform the pattern of appraisal. Automatic scoring in literary translation particularly can never capture the human professional judgment involved.

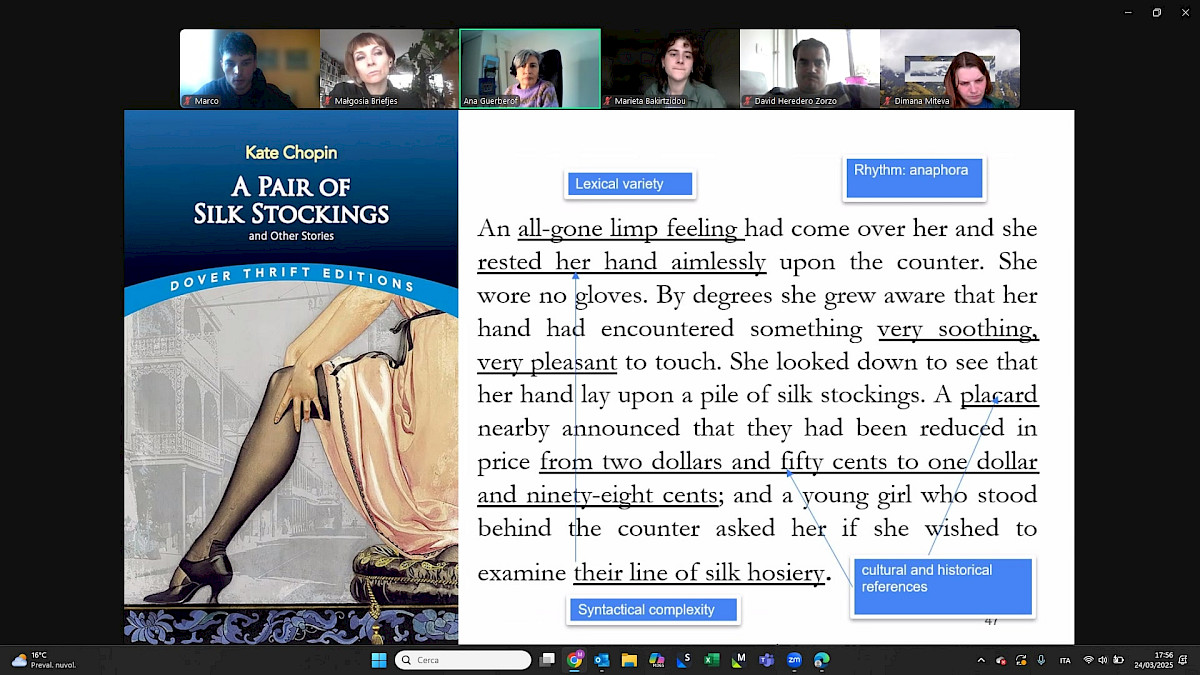

Professor Gueberof defined creative translation as identifying issues with the source text, generating multiple culturally based solutions, and selecting the most effective one to rebuild the original reader's experience in the target language. We learned how to identify creative shifts, including, the use of metaphors, puns and idioms, cultural references, neologisms, or regional dialects, including tone, punctuation, rhythmic adjustment and the translation of onomatopoeia, phrasal verbs, or wordplay.

They assist in measuring creativity—at least to a certain extent—and emphasize that translation is not an automatistic process, but a socially and culturally embedded action. Creativity, Ana concluded, does not emerge from the individual but from an interplay between the translator, the translator's surrounding culture, and the expectations of the target audience.

These courses have reinforced the idea that while computer tools—e.g., CAT systems, corpora, and AI—are valuable assists, they are not a replacement for the translator's judgment, imagination, or contextual sense, especially in literary translation.

Technology can assist, illuminate, and even stimulate. But it is the human mind which translates, makes decisions, and ultimately builds meaning—not just words.